An Introduction to Differential Privacy

Why should we care about privacy? The obvious answer is because vast amounts of data about people is being collected, stored and processed every second, for purposes that range from basic webpage performance optimization to deliberate mass surveillance. In 2018, an estimated 2.5 quintillion (2.5x1018) bytes of data was produced every day and so in 2020, we can safely assume that a lot of data is produced and stored daily. Alarmingly, much of this data concerns the actions and attributes of real people and where there is information about people, there are privacy and security concerns.

In my PhD, I work with a mathematical definition of privacy for databases and algorithms, called Differential Privacy (DP) [1]. DP represents a principled way of defining and measuring privacy in data collection and processing.

- DP’s View on Privacy

- An Example Use Case

- Formal Definition

- Strengths of DP

- Weaknesses of DP

- A Common Criticism of DP

- Why do we need DP when we already have encryption?

- Introductory DP Resources

DP’s View on Privacy

For any topic as complex and important as privacy, there is inevitably some debate about how it should be defined. Differential Privacy provides a mathematical framework for releasing information about a database while preserving the privacy of the individuals who contributed to that database. It is a formalization of Dalenius’ [2] notion of privacy for databases:

Nothing about an individual should be learnable from the database that cannot be learned without access to the database.

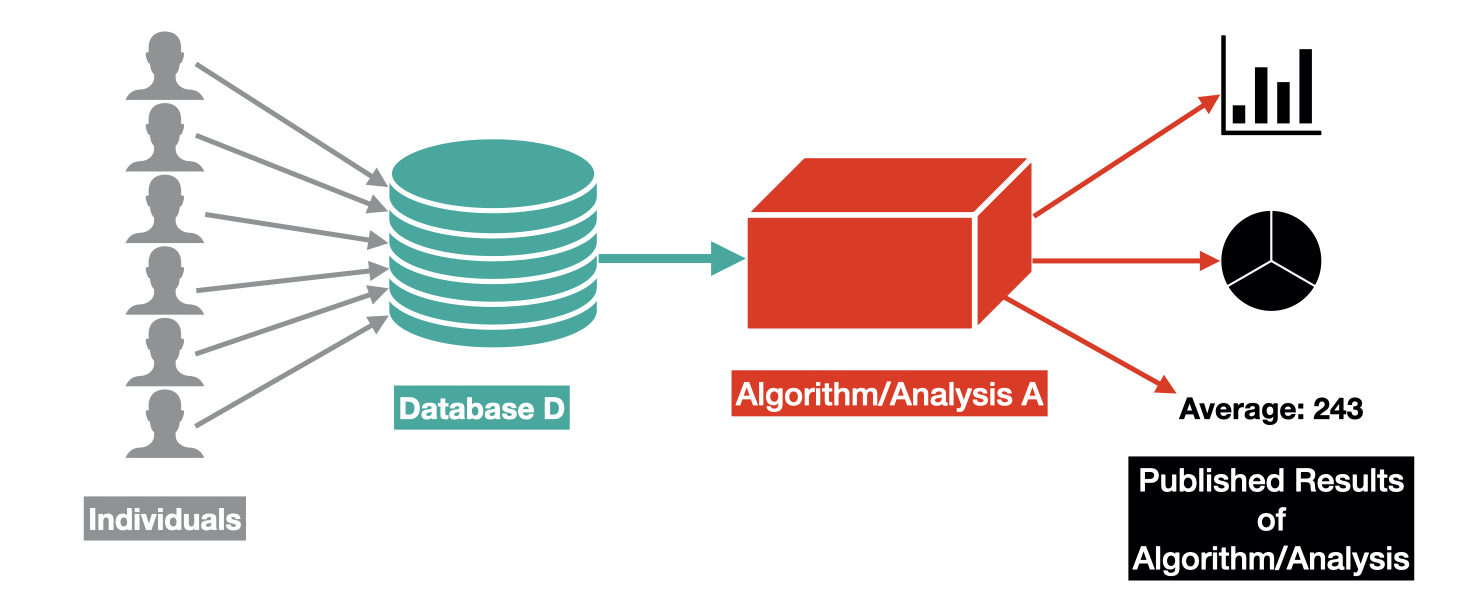

DP assumes that individuals each contribute a single row of data to some database D and provides a definition of privacy for those who contributed to D, given that an algorithm A releases some information about D.

For example, the published results from the algorithm A could be :

- The result of an analysis performed over D (e.g. the average age of people in D).

- A machine learning algorithm trained using D.

- A sanitized/privatized version of the database D.

Then at a high-level, Differential Privacy guarantees that it is very hard to reconstruct any individual row of data from D when observing the output from the algorithm A. The harder it is to reconstruct a row of data from D, the more differentially private the algorithm A is.

DP takes the view that if an individual’s information in some database D cannot be reconstructed from the output of some analysis or algorithm, then that individual has privacy with respect to that algorithm/analysis. If no possible individual row of the input database D can be reconstructed from the output of an algorithm A, then that algorithm is privacy-preserving.

An Example Use Case

Surveys collecting potentially embarrassing information provide a classic a use-case for differential privacy. Suppose we are collecting a survey of doctors within a hospital. We have scrubbed each doctor’s name and have recorded if they smoke or not. This information is important for the hospital’s insurance policy, and so it needs to be accurate. However, the doctors may hesitate to self-report smoking as they fear this information could be used as evidence that they do not follow published medical advice.

While we have scrubbed the doctors’ names, there is still a chance that we can learn about individual doctors from an analysis as simple as the proportion of doctors who smoke. Consider that some member of staff at the hospital happens to know the smoking habits of every doctor apart from 1. They can then easily reconstruct if the unknown doctor smokes or not.

While this example is overly simplistic, the risk of reconstructing data from scrubbed databases (or from published aggregate information) has been shown to occur in many more complex scenarios. For example,

- Users were re-identified from an anonymized netflix rating database [3].

- Input training images of faces were reconstructed using published machine learning models [4].

This is where Differential Privacy comes to the rescue!

Formal Definition

The formal statement of Differential Privacy states that when two databases are similar, then the distribution of possible outputs from a private algorithm over either of those databases should also be also similar. In this sense, it is conceptually close to the idea of stability from learning theory and can be viewed as a type of stability condition for the algorithm.

Neighbouring Databases: Two databases D and D’ are called neighbouring if they differ in at most 1 row.

Differential Privacy: A randomized mechanism M satisfies ε-differential privacy if for all neighbouring databases D, D’ and for all possible outputs S⊆Range(M):

P[M(D)∈S] ≤ eε P[M(D')∈S]

In plain english: an algorithm M satisfies differential privacy if for every possible pair of neighbouring databases D and D’ and for every possible output from M, then the probability that you get that output given M uses D or D’ is similar (where similar means within a multiplicative factor of eε).

One way of understanding this at a high level is that differential privacy requires similar output distributions for M whether M uses a database D or any possible database one row away from D. The definition essentially ensures that changing a single input datapoint does not have a large effect on the output of the algorithm, therefore making that datapoint hard to reconstruct regardless of what other information is known.

A popular relaxation of differential privacy, called approximate differential privacy[5], also adds an additive constant λ to the definition.

Strengths of DP

Differential privacy is the current gold standard notion of privacy, in fact it was rolled out in the 2020 US Census [6] and is used in industry [7][8] as well as academia and government. It was even mentioned during the set up instructions for my current phone [9]. Some of its many strengths are as follows:

- DP gives us a provable mathematical guarantee for privacy, as opposed to a potentially vague or ambiguous heuristic definition.

- Using its composition properties, differential privacy can be used to quantify the privacy loss for a database when it is used in multiple calculations.

- DP algorithms are immune to post-processing, meaning that a released private statistic or model cannot be made less private after-the-fact.

- The DP guarantee holds for a given database row, even if the attacker knows everything about the database apart from that row. This addresses previous issues with privacy definitions being vulnerable to the use of external information (e.g. by combining the releases analysis with information from other public databases).

Weaknesses of DP

As with any definition, DP also has some weaknesses. However, many of these have been addressed by later extensions of DP. Its weaknesses include:

- Ensuring privacy often results in decreased accuracy in comparison to the non-private version of an algorithm. For some queries this accuracy cost can be very large. For example, if we want to release the maximum value found in a database when the data can take a very large possible range of values, then changing a single datapoint can change this output significantly. Making this query private can require a significant loss in accuracy.

- If you run an algorithm twice over a database, in differential privacy your privacy guarantee for the database gets weaker. This means that it can become hard to maintain a reasonable balance of privacy and accuracy when multiple queries need to be made.

A Common Criticism of DP

Harsh criticisms of DP often arise from misunderstandings concerning the view DP takes on the fundamental question of what privacy means. Critics state that DP does not work for correlated data.

Indeed, as it becomes increasingly infeasible to know for sure what information is available elsewhere, differential privacy only ensures that a specific secret held before its use in the result of an algorithm or the release of a database will not be revealed by the released database or computation. It does not hide information that could be learned about an individual entry by observing the rest of the database. DP is intended to quantify and limit the amount of information that can be learned about an individual by adding their data to a database and therefore protects against secrets which could be disclosed by adding that individual’s data to the database but that would otherwise remain private. As outlined by Frank McSherry in his brilliant blog posts on differential privacy, given information about a person’s genome, 100% of the information is private in some sense. However, when an individual adds their own personal DNA information to a database, 98% of this information is common to all humans. Therefore, in reality only 2% of the information is a secret that could be kept by withholding an individual’s data from the database. DP obscures 2% of the individual’s information, but it cannot guarantee protection for the 98% that can be found in other records.

Why do we need DP when we already have encryption?

A relatively common response to the idea of using differential privacy is: we already have security and encryption to protect data, we don’t need privacy as well. In fact, security and privacy solve different (although ethically related) problems. Security protects data while it is being stored and used internally by the algorithm. Privacy protects the data from inferences made using the publicly published result of the algorithm.

For example, if we have the dataset {2, 3, 4, 5} and an averaging algorithm. Security will protect the raw dataset and perhaps obscure that raw dataset from the algorithm during computation by the algorithm. Privacy instead implies that when the algorithm publishes the average value (e.g. 3.5 plus a little noise), then someone observing that value shoud not be able to infer that there was a 5 in the underlying dataset.

Introductory DP Resources

- This book is the go-to introductory text on Differential Privacy by two giants of the field (including its inventor, Prof. Cynthia Dwork).

- This youtube video by Simply Explained is a great introduction to the intuition behind DP.